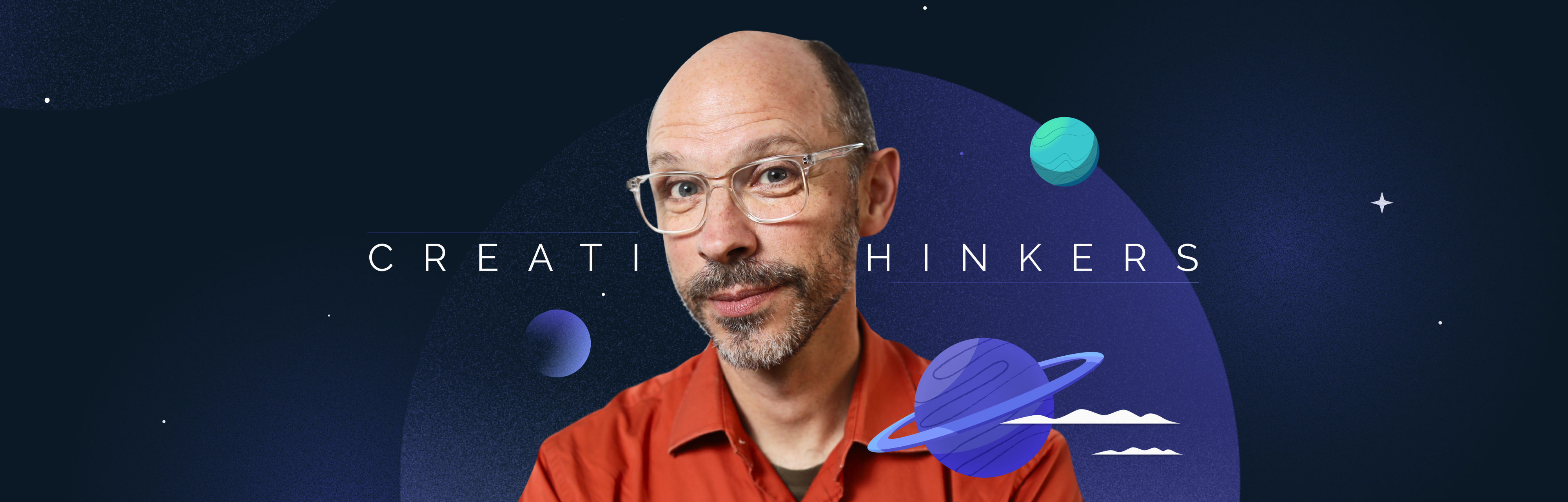

Scott Welliver: How Open Design Transforms Culture at Abstract

Superside is an always-on design company that delivers top-quality creative at scale to enterprise teams. This interview is part of our recurring series “Creative Thinkers,” where we talk to amazing people about career challenges, the transformative role design has played in their lives and what it means to be creative.

Introduction

Scott Welliver is obsessed with solutions. Over 20-year career in design, Welliver, now a Design Advocate at Abstract, has learned through experience that surrendering ego can often lead to the best, most effective solutions to any design problems that present themselves. Nothing should be created in isolation, says Welliver, and when you open yourself up to being transparent with the design process, good things are going to happen.

"I’ve always had this entrepreneurial fascination with making things and solving problems."

When I was a kid I used to race remote control cars, and I saw an opportunity to make these cotter pins, which would keep the shell of the car on the body of the car itself. And I would try to sell cotter pins, which are just little wires that are bent, instead of trying to sell lemonade. They weren’t a big seller—I had no understanding of the “market,” but a desire to tinker and build and make and problem solve.

My mom was an administrator for a few different companies, and my dad was an engineer. Neither of them could really align on what this fascination with solving problems would mean for Scott.

I ended up going to college at Penn State University, where I thought I was going to go into anthropology. So, I’m in my very first class and the teaching assistant starts describing her summer experience, which was somewhere in the Middle East, where she’d spent the whole time digging in the hot sun. And I'm like, "Dude, where do you get the cool hat from Indiana Jones, and the whip, and when did we start fighting the Nazis?"

I really had the wrong idea about getting into anthropology. But it caused me to immediately ask myself, What are you going to do? I’d always thought about making creative things as something that I’d do, so I flipped over to film studies and literature study. I figured these were the two areas where I could make things that would actually make sense.

I was doing literature stuff and some film stuff in school, when a friend of mine started a literary magazine. It went nowhere. But when you write a bunch of stuff someone has to lay it out. My friend was the writer. I was more interested in figuring out how to make layouts using a software tool. It was a bootlegged copy of QuarkXPress—you’ll need to carbon date me for my prehistoric age.

So that was really the first time that my inner passion for design, or making things, found a place to express itself. I was just really getting into taking drawing tools and making things with them. But I honestly didn't know what to do with any of that.

When I graduated college in 2001, I eventually ended up getting a job in marketing at an education company, and they would be like, "Scott, we need to hire somebody to design an ad for us...can you just mock it up?"

I was almost always the person who raised my hand and said, "Even if I don't know how to do it, I’ll figure out how to do it." In my fascination with the problem, I’ll have an idea where the solution is, but I don't know how to get there yet. So I'll work to figure that out. For better or for worse, that underlying theme has been with me all my life, particularly in my career.

Click to download this Scott Welliver-inspired pattern as an Adobe Illustrator file.

"In isolation, your best-intended designs can fall flat."

The Indisputable Value of User Research

So I was consistently volunteering and creating—this is at the same time that the Internet and the product design space was really being created. We didn't know it then. We were just building tools that would make solutions for the problems that we saw.

I had a few design consultancy stints, that helped me figure out how to work in problem spaces, and what to do with them. And ultimately, I moved away from just drawing things, to building solutions.

In 2012, I worked for a startup here in Philadelphia called TicketLeap. I was hired as the director of UX, but there was nobody other than me in the company who did design (though, to be fair, everyone there had a keen appreciation for the problem and for great designers). So I inherited a team of zero, and by the time I left, we had two other people.

The project that we were working on was basically self-service ticketing for organizations that ran small events, like local theaters, or production companies. Instead of using Ticketmaster or some other very large ticketing company, they could do it all by themselves. At the time we had a lousy, lousy mobile-slash-tablet app. It was my first time considering, How does this product actually get used in real life? It sounds almost crazy to say, but there was a time when I was designing without understanding how someone would actually use it, which is so counter to user-centered design. Instead, it was designed-centered design.

Fortunately, I had a tight relationship with the end users of the product and we quickly realized that it wasn't working in the way that was expected. So we were like, "Let's reformulate it. Let's just go in, and watch people use it." This is observational research—the real meat of discovering insights by observing customer use. I had designed an interface where the final action button was in the bottom right hand corner. And when we observed people holding their iPad devices, they’d do it in this landscape way, with their thumbs low, and they’d inadvertently tap that finalize button. Originally, we’d had it in a place where they weren't touching it and then, without testing it, I’d made the decision to move it down to the place where it became an obstacle.

You can use all of your gut and training to some degree, but your best intended designs can still fall short if you don't observe someone actually interacting with it. That incident sort of solidified this moment for me and my team, where we decided to just be very deliberate, considered and open about the design decisions we made. When you do that, the arrogance gets sucked out of the room as soon as you see someone failing using your product. I've appreciated that every time my arrogance has shrunk. There’s a lot to be said about observation, and collaboratively understanding the problem space, because in isolation your solutions can fall flat.

Click to download this quote as desktop wallpaper or for sharing on Instagram stories.

Collaborative Design: A Necessary Shift

More recently, I’ve been building teams and building workflows for teams: Mentoring folks from stage one to stage two, taking someone from where they are to where they could be, which is the design process.

I joined Abstract in 2019, but before that I worked at Comcast, a Philly-based telecommunications company for close to four years. I had the privilege to lead a number of teams at Comcast—really, really fantastic teams—and I think the success we had is not necessarily measured in the products that we built but in the fact that those people are better at what they do now, because of the time that we spent doing things together.

Now, as a Design Advocate at Abstract, I’m in a very different but also very familiar role. Basically, Abstract is a platform that brings visibility to the entire design process by centralizing files, stakeholders, decisions, and assets needed to deliver products at scale for leading design teams. So traditionally, with Sketch, or Adobe XD, or any kind of drawing tool or creating tool, we would make files, and have lots of files. And there'd be no way to know if we're making progress, where the latest feedback lives, or what changes were happening within those particular documents. All of those answers were scattered across disconnected tools. And so, a few years ago, Kevin Smith and Josh Brewer, who founded Abstract, borrowed the vernacular of our development partners, who have this model called Git. And Git is a making a branch or kind of like, a workspace, off of your source control. So you have a source that's protected. And then you're going to use a workspace, which is basically a one-to-one copy of everything. And I can do all my changes there, and I can have approvals, and then I can merge that back into my source, so I actually do have a source that's true. We call it a branch, and it can really change the way you consider designing at scale.

And so, I was a part of a team that brought that into Comcast, to help us (1), know exactly what's true, and (2) to be transparent and open about the design that was happening in our organization.

Those two things can actually change the dynamics of teams working at scale: knowing what your partners are working on, as well as what people that you don't typically run into in to day after day are doing. Abstract creates that transparency between those two groups. But it also involves a bit of a mindset change: We’re no longer designing on files that are just mine; now we’re designing on files that are ours. We're designing our experience.

And that's about taking away ego. We don't have to be so private about the work that we're doing. We can do this in collaboration. It not only opens up collaboration between designers, but also, it opens up collaboration with the other stakeholders in the product design process or the tech-building process. That visibility is important because it demystifies the design process for the entire organization.

Because that open, collaborative mindset is a bit of a change for many design teams, it requires a bit of workflow description, consultation and advice. And that's where the Design Advocate comes in. We’re mostly dealing with someone who says, "Okay, wow, that that is not how we used to do things, but I find a lot of value in using this new model." And then there's also the other side, where it's like, "I don't know if I'm doing the right thing. Can you help us decide if that's the right thing, based on your wider exposure, to this new toolset and mindset?"

That's where Design Advocates get to come in. We’re really here to help teams do their work better, and at scale, using Abstract at the center.

Lightning Round Q&A

"We can’t work in polarized bubbles."

This Design Isn't Mine. It's Ours.

For many years I think design has had workarounds, given the limited digital toolset we’ve had at our disposal. What we didn't have were predictable workflows. Now we have tools that manage those workflows without necessarily forcing you to get away from all those familiar workarounds.

You can do work at scale and speed and with full transparency—the trick is, you have to change your mindset to say, "This is not just mine, it's ours."

Some of the detractors I encounter have good reasons, but some of them are a little bit flimsy, and based on fear. Designers often say we want to be forward thinking; we say that we want to do very progressive things, but sometimes we don’t necessarily do that.

And some teams are just not built that way. Others aren’t led that way. Some teams just saw the idea at a conference, but they don't know how to actually mechanize the process.

That's where I get to either speak truth or really be like a good therapist. There's a lot of pressure to deliver right now, because designers have a lot of momentum. They’ve got a seat at the table, which means they need to be able to demonstrate that design is more than a frill—it has measurable impact on the business. In my experience, the delivery process has usually been more like, we do stuff in a black box and then have a big dog and pony show that ends with a big reveal. But that doesn't really bring your stakeholder along through your thought process, doesn't really show your work very well. It’s only revealing the final state. Beyond that, sometimes developers are handed the baton only to say “this is nutso.” If they’re involved in the design work earlier we can actually move faster by designing for feasibility.

We haven’t had common tools that allow people to see the work a designer is doing; instead we just get to see the final product. Tools like InVision, Abstract and Figma are building our shared vocabulary with our stakeholder teams, which I think is helpful.

Signoff on designs is immediate, because everyone bought in along the way. Even if there was disagreement at some point, you would have worked that out before you got to that final reveal. So, to me, it's a non-starter to not collaborate. It's not always easy, I get that. But we can’t work in polarized bubbles. I believe the antidote is generosity. And to be generous is to be open, as far as I'm concerned.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Designed by Superside, inspired by Scott Welliver: "Something sturdy, minimalistic and indoorsman-looking". Download this free font.

You may also like these

Peter Merholz: How Agile Can Turn Designers Into Pixel Pushers

IntroductionPeter Merholz is an experienced design executive and author who's become a master at building effective design teams. The one challenge he keeps witnessing is the negative impact that Agile transformations can have on design. The solution? We need to strengthen our design leaders—they need to push back on the systems that are trying to turn their teams into cogs in a machine.I just didn't know what else you would do with computers. It wasn't until I was a few years into college that I became aware of human-computer interaction and those types of things. If you had met me in high school I would've said I wanted to go into advertising. So I had some sense that I wanted to be in a creative field.I ended up getting a BA in anthropology from UC Berkeley. Part of the reason I pursued an anthropology degree was that it allowed me to take classes in videography—essentially filmmaking—because Berkeley didn't have a real film program. So I’ve always had some interest in those acts of creation, but as the anthropology degree suggests, I really had an interest in understanding humans.

Jenna Bilotta: The Biggest Design Problem to Solve is Diversity

IntroductionJenna Bilotta, the VP of design, Premium, at Spotify, knows what it’s like to feel alone at work. In one of the first meetings she had as a young designer working for Google, she was the only woman in a room of 18. That sense of isolation followed her from Google to YouTube to Dropbox, but it never diminished her passion for effecting change along the way and, now, at the leadership level. After all, she says, diverse perspectives drive the best design and that’s what we all want, isn’t it?When I was little, I made my own paper dolls with full wardrobes. I was always drawing and creating little creatures and environments and worlds for myself. When I was a little bit older, I was certain I’d become an architect. So I started drawing the houses in my neighborhood and other buildings, but at some point I realized the actual discipline of architecture was far too precise for my taste.When I was in high school in the mid-90s, computers were just starting to become more accessible to households and families outside of businesses. We got a computer in the art room and I thought it was the coolest thing ever. It had, like, Photoshop 2. I didn't really understand what digital art was, but I was definitely interested.

Anne Purves: The Ongoing Evolution of DesignOps at Pinterest

IntroductionAnne Purves never meant to become a DesignOps guru, she came to it honestly. A creative thinker with a flair for process, Purves honed her DesignOps chops like so many do—by working through tensions between design teams and spending time navigating the agency life. Now the Director of Design Operations at Pinterest, Purves is empowering design leads to take more ownership over their domains. It's helping to solve high-impact issues for the business, but is it the future of DesignOps?You've heard of the Packers? It was a small town upbringing so I didn't have a ton of exposure to design but I've always been interested in the arts. I was into performing and choir and theater from middle school through high school. I just felt like, I like this, these are my people. I was never very into math and science, and more analytical subjects never really interested me. In the arts I really came alive, and in things like creative writing and English I thrived and found my stride.Of course, I took a hard left when I went to college—I actually ended up in business school. I was still interested in performing and I was in singing groups and things like that, but when thinking about what I wanted to do, I thought advertising and marketing were pretty cool and would allow me to be a little bit more creative and also make a living.