Jasmine Friedl: How Intercom Creates Inroads for New Designers

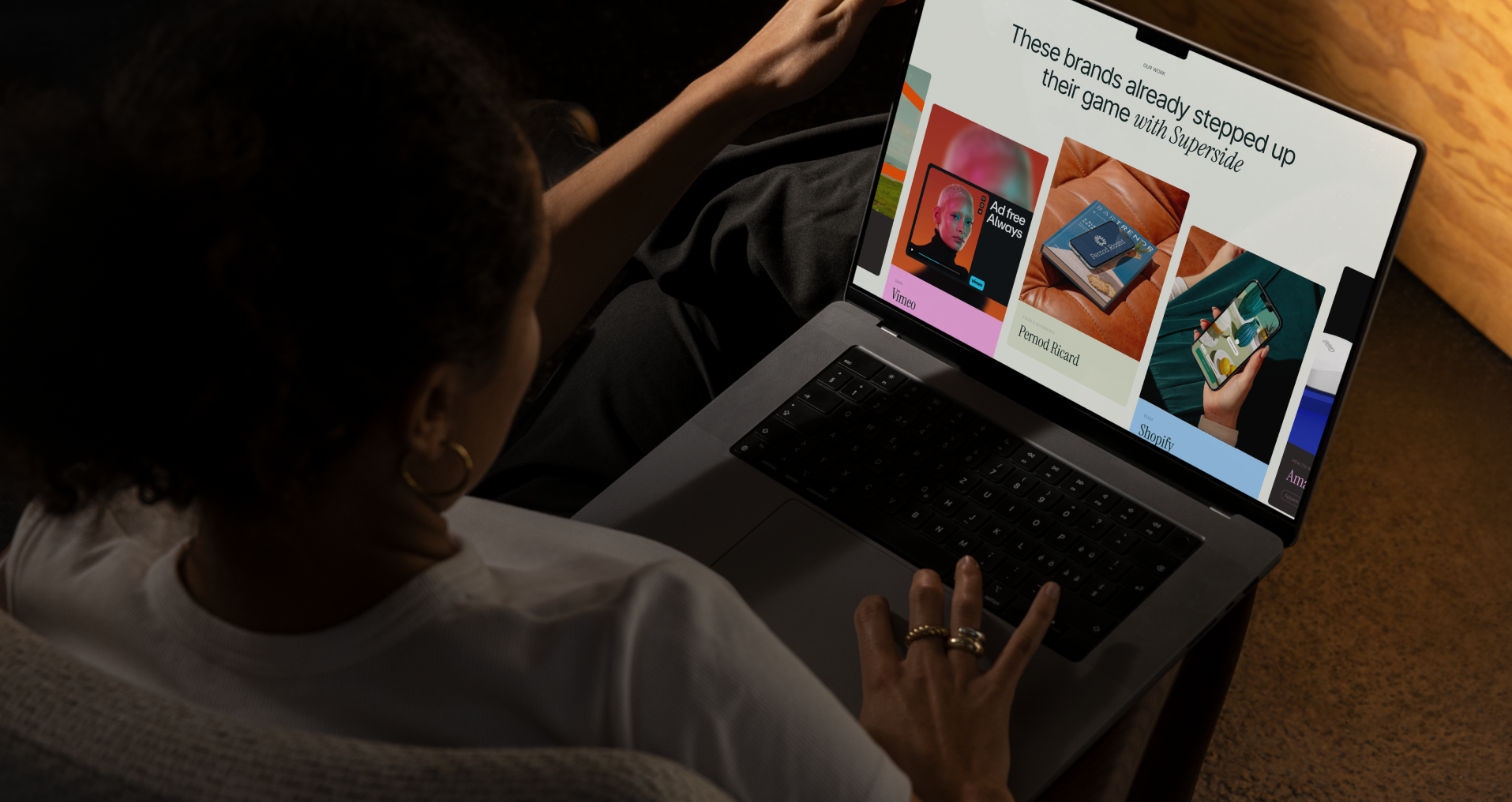

Superside is an always-on design company that delivers top-quality creative at scale to enterprise teams. This interview is part of our recurring series “Creative Thinkers,” where we talk to amazing people about career challenges, the transformative role design has played in their lives and what it means to be creative.

Introduction

Jasmine Friedl knows how hard it can be to land that dream job. Sure, she’s the Director of Design at Intercom today and she’s led teams at Udacity, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative and Facebook, but her career in design has never come easy. Hard work, risks and a lucky break are what helped her really get a foot in the door. And now that she’s doing the hiring, Friedl can see the barriers to young talent more clearly than ever—from criteria-free recruiting to an overreliance on high-profile experience. But she’s not playing that tired old game. She’s changing it.

"I was born in Northern Wisconsin in a shack on someone else’s property."

We didn’t have a lot. My parents are super conservative—religious—and that actually plays a lot into who I am today. I went to private schools: a Mennonite school for grade school, and a Christian school for junior high and high school. There were 16 people in my graduating class, maybe 75 in the entire high school. I came out feeling that you could be anything or do anything if you just wanted to, mostly because in a school that small, you had access to experiences that might have been limited with more students, and therefore more competition.

When I graduated, I thought I was going to be a mechanical engineer; that's what my brother had gone to college for, and it seemed legit. I went to Iowa State University and took calculus and a bunch of science courses. Then, on a whim, I decided I wanted to take an art class too, some drawing 101 class. To get a seat in one of the sections, you had to enlist in an art major, so I chose graphic design. I ended up being pretty decent at the whole design thing—was in the top five in the program for my year, won some excellence awards and all that. It hadn’t been my intention to be a designer then—I still wanted to try everything, be a generalist like in high school—but when I got that recognition for it, I was like, "Okay, this seems feasible."

Find this on Giphy at SupersideJasmine

"I’d really forgotten that I had something that moved my heart."

At the time in the late 90s, graphic designers were quoted at making around $65,000 a year. That seemed like a lot of money to me because of the state that my parents had been in: my mom was a stay-at-home mom and my dad was often unemployed. My target in a career was to make as much as my dad did on a good day, and this was nearly double that.

I slogged through college, and found myself in my first serious relationship with a guy from school who moved out to San Francisco. I was intending to get an internship the first summer I visited him in SF and did a bunch of interviews. People were like, "nice work," but they were basically pity conversations: them wanting to be helpful but not having any openings. At the time, San Francisco was reeling from the dot com bust, and everyone was letting go of their teammates and not hiring. I needed an alternate plan.

I ended up working as a brand rep at Abercrombie & Fitch in the downtown shopping center.

I finished my degree in graphic design back in Iowa and graduated in 2002 at the top of my class. I immediately moved out to San Francisco permanently—did the whole two checked suitcases and a carry-on thing. But I had no idea how expensive rent was. I was down to zero before I knew it, so I had to get the first job that I could find. And that job was working as a management trainee at a rental car company, and later becoming a manager.

For a religious girl in her 20s—who came out to San Francisco and was suddenly in this “work hard, play hard” environment—it was difficult. I was working 50 plus hour weeks and getting paid nothing. I believe $34,200 was the quoted salary, and I initially was proud of that because it hit my target. But the culture was morally and mentally destructive.

I clung to the job because it was all I had to make ends meet but it didn't make me a better human.

After six years, I’d finally had enough and I left. I was completely burned out. The job and much of the leadership was mentally abusive. It’s a special sort of trauma that creeps up on you: starts with micromanagement and unrealistic expectations and slides into this sort of conditioning where you’re led to believe you won’t be able to find a job anywhere else, and that the conditions that become the norm are not only acceptable, but desirable. I’m talking about insane circumstances like working in an office without a fully functioning bathroom, being charged personally for vehicle expenses, constant sexual harassment from peers, managers, and executives, unethical business practices, and things I’ve probably buried in the depths of my psyche. And you’re supposed to be proud of these things, because it’s your company culture. You forget that what you have to offer is something special, and that you are worth more.

I’d really forgotten that I had something that moved my heart, that I had come across something special in college that I deeply connected with. And perhaps in college, I didn’t know that I was actually deeply connected to design, because I hadn’t yet felt that severe disconnect that I did in this job experience.

Click to download this Jasmine Friedl-inspired pattern as an Adobe Illustrator file.

Design: This is What I’m Supposed to be Doing

Around 2007, I started looking at grad school design programs and applied to The Academy of Art University in San Francisco. I took a tour of their building on Montgomery Street, on the fifth floor, where they have their graphic design department. As I was walking around, looking at the student work that was pinned up on the walls, I literally got tears in my eyes. This was me. This was what I was supposed to be doing.

I’m not gonna lie: There were a lot of challenging moments at the Academy of Art. I had a love/hate relationship with my instructors. They would push me to the brink, and I would go home and have complete breakdowns and just cry and drink a lot of wine and then flip the laptop back open and get the work done. It’s hard to take on challenges sometimes when you’re already a little broken.

But I learned so much there. It's not even necessarily the design skills that I benefited from most, but rather developing a tenacity that I’d never really built up before.

The associate director of the program at the time, Hunter Wimmer, put me in for an internship at a place called Office in San Francisco. They were actually two Iowa state grads who had their own 12-person design studio. I had an interview with them and I thought it went really well. They ended up giving the internship to a friend of mine, Johnny Selman. He was amazing, he absolutely should have gotten that internship. But I was devastated. I was working full time at a retail gig, trying to get through full time school, and I just needed a break really badly at that point.

Then they called me back for another interview. They’d opened up another internship, and I got it. I ended up working at Office for a year and a half. It was a top brand studio in the city—we worked with Disney, eBay, Fanta and some really big names. I got to really see firsthand how brand was done and I was able to contribute substantially too.

I was still working through my thesis project, and I decided that I wanted to design an app on budgeting, which was kind of nuts because I was in a primarily print program. That project was what really got me into product design; it actually landed me my first role on the UX team at Hot Studio, which was this amazing little agency in San Francisco. Maria Giudice, who owned Hot Studio, ended up being such a wonderful, authentic mentor and friend to me. She’s truly one of the people I credit for helping me succeed. Eight months into that job, we ended up being acquired by Facebook.

I did a lot of stuff at Facebook: I was the first designer on the Payments team; I learned about growth design. I was the lead designer on Payments in Messenger. Safety Check was a really special project too that I led, which was developed from a hackathon.

But Facebook is also where I found my love for EdTech. We had a personalized learning platform that we were working on with Summit Public Schools called the Summit Learning Platform. But it didn’t really fit in with Facebook’s mission, so after the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI) was established, the project moved there. CZI had a mission around making sure that each and every child in the world has access to personalized learning and examining equity in education. To work for CZI, I’d have to leave Facebook. I did—and it was a no-brainer. I just wasn't going to go back and work on core Facebook. There weren't things there at the time that interested me in the way that education did.

Click to download this quote as desktop wallpaper or for Instagram stories.

"I wanted to be inclusive and make sure that everybody had a voice."

An Unintentional Entry Into Management

While this transition to CZI was going on, my manager went on maternity leave and left me in charge of the team. It caused some friction because it was never formally announced and some teammates had a, “Why you and not me?” reaction. Then she decided not to come back after her leave, so I took on the role of figuring out what design would look like at CZI.

We had no design manager, and we were starting a design team fresh, since there was no technical team at CZI. And because we were in this sort of state where everyone’s like, "Who's the team leader?", I wanted to be really inclusive and make sure that everybody had a voice and that decisions were being made collaboratively.

I made a list of all the hiring processes that we’d used at Facebook and I went to the team and said, "How do we feel about these? Would we want them to stay the same? Would we want to change them now? Are they good enough?"

It was actually my unintentional entry into management.

We didn’t have a design recruiter either, so I became the recruiter. I wrote all the interviewing processes and the guides and the rubrics in partnership with Paul Derby, a researcher who was also joining CZI from Facebook with me. We hired two or three new designers and two or three new researchers and built out the team.

I was one of the last people to formally leave Facebook after a six-month transition. Once everything was wrapped up on the Facebook side, I worked one day at CZI and took a two-week planned leave. I was wiped out from the transition. I had been recruiting for someone who would basically be my boss—the director of design—and had done so much sourcing on LinkedIn, the platform was finally like, "Jasmine, are you actually looking for a director role?"

That’s how I ended up finding this listing for a director of design at Udacity, a tech education company. And I looked at it and I was like, "This is really odd because this is exactly what I'm doing at CZI and it's in EdTech, still focused on equity and accessibility of education. It's in my space. They need me. Why not apply for this?"

I had previously had a conversation with my boss and asked if he could make me a manager; that’s basically the job I’d been doing but his response was that he just wanted to wait for that new director to come in and make that decision. So my career was being put on hold. I never even thought to ask for the director role myself—I saw too many gaps. I saw my lack of confidence. I saw the room I had to grow. And I think I was just being a little bit conservative.

So I interviewed at Udacity and nailed it.

They made me an offer. It was an "Oh shit, do I really want to do this?" moment. It meant an enormous pay cut. But it was also about considering where I could grow the most, because I wasn't getting the opportunity at CZI. I firmly believe that in order to be a good leader, you have to invest in your own growth first.

I decided to take it. I worked for Udacity for a year. I had the precise experience needed for the role. I did a lot of hiring and built up a team again. I got design operations in place. I was starting to get involved in product strategy at a meaningful level. Eventually, I was offered a role that was pretty high in level but it wasn't a design role, it had to do more with company strategy. I declined because it was counter to my own growth goals and the path I saw myself taking, and the impact I wanted to have through these things. Once I said no to the opportunity, I suspected that my future was going to be limited. I wanted to go to a place that aligned more closely with my values.

Lightning Round Q&A

Eliminating Bias in Hiring: It’s a Leadership Responsibility

So now I’m the director of design at Intercom. I lead the product design team in San Francisco. A good part of my job so far has been people management: making sure my teammates are set up well, have the right coaching, have the right guidance and are feeling engaged in their day-to-day.

Everything I've ever done in my leadership career has been people first. It's how I work. It's how I learn. It's where my heart is. And I firmly believe that if you invest in people’s experiences and development—if you value them—they will do anything for you. But if that investment goes missing, you can't get the same outcomes.

Hiring and creating inroads for new designers are major issues right now. When I started at Intercom, I noticed that our hiring practice wasn't super thorough—we didn't have an established and practiced criteria by which we evaluated candidates. I thought: Why wouldn't we just take those things we hold people accountable for in our performance rubrics and use those criteria for hiring? So I crafted a process that uses our leveling rubrics throughout the hiring process. By following those rubrics, you're really looking for behaviors or examples from candidates that demonstrate their competencies based on what’s required for the role. We call these “look-fors” that we focus on during the interview.

Anytime we're evaluating a candidate and we're not using some sort of established criteria or the rigor of our system—whether it be through standardized questions or whatever—we're opening a door for bias. Bias prevents people from getting roles they’re qualified for. Obviously this affects women and minorities more than it does our white and male population. We have to start to paying special attention to this, and we actually need our white males to be the advocates of processes that minimize bias, because they’re frankly the majority.

"Bias prevents people from getting roles they’re qualified for."

Criteria-less hiring is everywhere, and it tends to go on because I actually don't think designers are taught otherwise. For all the rigor we had at Facebook, I think back on all the interview feedback I wrote there and I'm embarrassed for it. I would try and pull on irrelevant threads that I observed. I said no to so many amazing designers that are at Facebook right now because I was trying to have a voice and I was trying to be a good interviewer, but I didn't know how to do it yet: didn’t know how to translate what I observed against what we required in our roles. We had a criteria, but we didn’t all know how to use it. Sure, we know we needed to look for a prescribed set of skills, but we didn’t take the time in training to calibrate on what the skills looked like in practice. And we had people doing hundreds of interviews who may not have mastered the skills themselves. It’s a tricky thing, when your best designers are knee deep in high priority projects, so you send in the second string to interview. All of the problems this creates can be circumvented with great processes, training, and accountability.

This is actually a leadership responsibility. If we don't introduce the need for great interview facilitation, feedback, and decision making, no one interviewer—especially if you're at a big company and there's hundreds of interviewers—is going to be able to successfully advocate for this. You need systemic change to be able to do this.

This happens all the time: you’ll see somebody who has a Google on their resume and the response is: "Cool, let's screen them." And then you see somebody who has a no-name startup on their resume and it’s more: "I don't know about that." And you have no idea how skilled either person is. The person from the big tech company might be on their way out and the person from the no-name startup might be a rising superstar.

I think part of creating inroads and momentum for newer folks is just having an openness for people who don't fit these sort of high-profile molds. At some point we have to figure out how to help those new designers find their footing and find their way. Otherwise, we end up with a bottleneck where everyone’s stuck at senior (senior pathing is something else we have to figure out), and we don’t have distributed team shapes.

I feel like we're just sort of passing around the same, more experienced, designers and, if we’re lucky, we find some that tick off the underrepresented minority box. That is the wrong way to do this. We actually need to be nurturing and intentional about creating our next generation of designers by taking a chance on, then supporting, more junior people. That's how we fill all these roles. And that’s how we discover new talent.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Designed by Superside, inspired by Jasmine Friedl: "A little messy, some wrong angles, but 100% authentic." Download this free font.

You may also like these

Peter Merholz: How Agile Can Turn Designers Into Pixel Pushers

IntroductionPeter Merholz is an experienced design executive and author who's become a master at building effective design teams. The one challenge he keeps witnessing is the negative impact that Agile transformations can have on design. The solution? We need to strengthen our design leaders—they need to push back on the systems that are trying to turn their teams into cogs in a machine.I just didn't know what else you would do with computers. It wasn't until I was a few years into college that I became aware of human-computer interaction and those types of things. If you had met me in high school I would've said I wanted to go into advertising. So I had some sense that I wanted to be in a creative field.I ended up getting a BA in anthropology from UC Berkeley. Part of the reason I pursued an anthropology degree was that it allowed me to take classes in videography—essentially filmmaking—because Berkeley didn't have a real film program. So I’ve always had some interest in those acts of creation, but as the anthropology degree suggests, I really had an interest in understanding humans.

Jenna Bilotta: The Biggest Design Problem to Solve is Diversity

IntroductionJenna Bilotta, the VP of design, Premium, at Spotify, knows what it’s like to feel alone at work. In one of the first meetings she had as a young designer working for Google, she was the only woman in a room of 18. That sense of isolation followed her from Google to YouTube to Dropbox, but it never diminished her passion for effecting change along the way and, now, at the leadership level. After all, she says, diverse perspectives drive the best design and that’s what we all want, isn’t it?When I was little, I made my own paper dolls with full wardrobes. I was always drawing and creating little creatures and environments and worlds for myself. When I was a little bit older, I was certain I’d become an architect. So I started drawing the houses in my neighborhood and other buildings, but at some point I realized the actual discipline of architecture was far too precise for my taste.When I was in high school in the mid-90s, computers were just starting to become more accessible to households and families outside of businesses. We got a computer in the art room and I thought it was the coolest thing ever. It had, like, Photoshop 2. I didn't really understand what digital art was, but I was definitely interested.

Anne Purves: The Ongoing Evolution of DesignOps at Pinterest

IntroductionAnne Purves never meant to become a DesignOps guru, she came to it honestly. A creative thinker with a flair for process, Purves honed her DesignOps chops like so many do—by working through tensions between design teams and spending time navigating the agency life. Now the Director of Design Operations at Pinterest, Purves is empowering design leads to take more ownership over their domains. It's helping to solve high-impact issues for the business, but is it the future of DesignOps?You've heard of the Packers? It was a small town upbringing so I didn't have a ton of exposure to design but I've always been interested in the arts. I was into performing and choir and theater from middle school through high school. I just felt like, I like this, these are my people. I was never very into math and science, and more analytical subjects never really interested me. In the arts I really came alive, and in things like creative writing and English I thrived and found my stride.Of course, I took a hard left when I went to college—I actually ended up in business school. I was still interested in performing and I was in singing groups and things like that, but when thinking about what I wanted to do, I thought advertising and marketing were pretty cool and would allow me to be a little bit more creative and also make a living.